What happened, in brief

That time Israel kidnapped me

I’ll be writing more soon enough; it’s what I missed most in prison. But here, briefly, is where I’ve been.

I was in Tunisia for two weeks from late August, preparing to sail to Gaza with the Sumud flotilla. It didn’t work out, so I wound up going to Italy instead to depart from Sicily with the second flotilla organised by Thousand Madleens and Freedom Flotilla Coalition. We left on 27 September. As we sailed, news kept getting worse of Israel levelling Gaza City and an incipient ‘peace deal’ involving famed sage of the region Tony Blair.

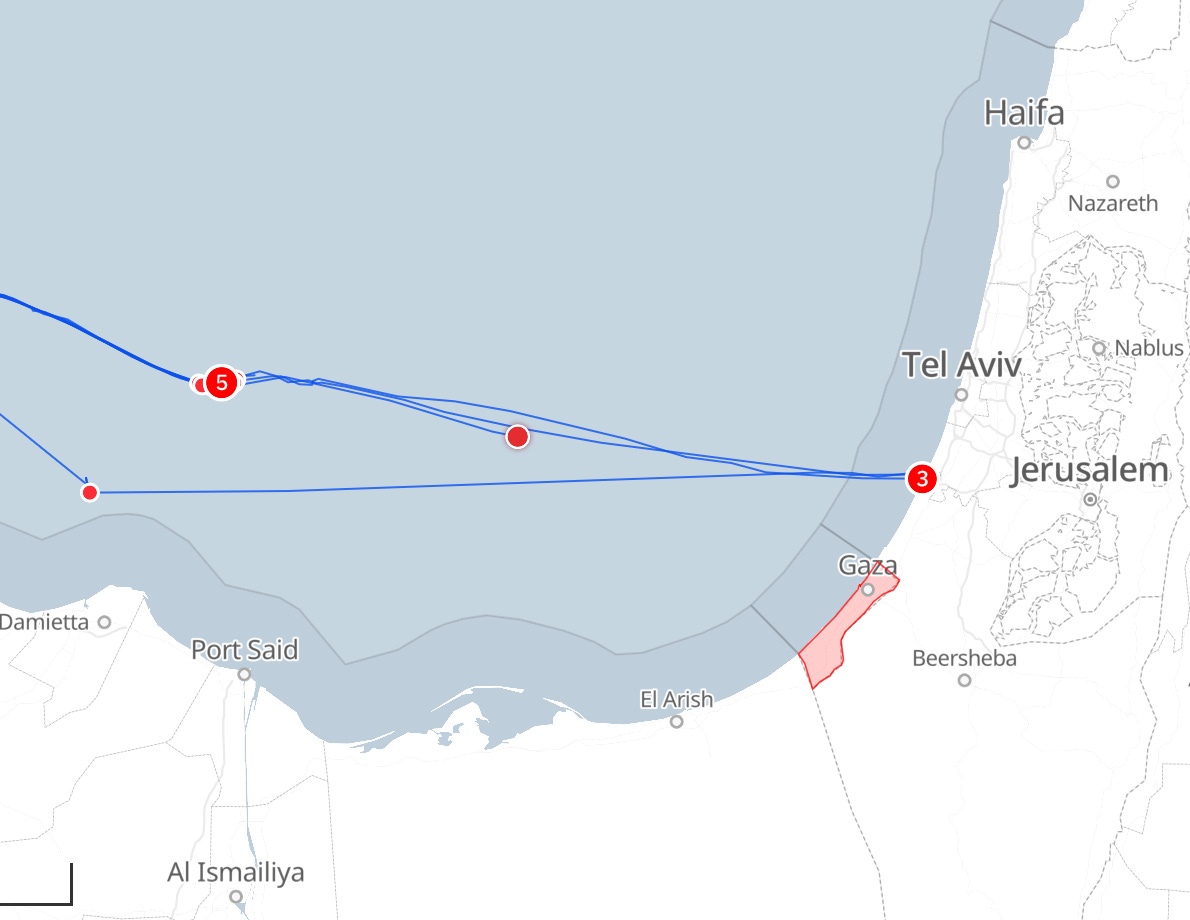

On 8 October, 5am, I went to bed having finished my night watch shift. We’d seen speedboats on the horizon but thought it was likelier to be an intimidation attempt than imminent abduction, given how far we still were from Gaza. Just as I’d settled down in my bed above the couch, one of our sailors called that they were coming, go outside, not a drill. They didn’t even say they were Israel, let alone do their customary ‘You can give Israel the aid to distribute, thereby undermining your entire point about Palestinian self-determination, and turn around’ announcement; they just yelled at our captain to stop the boat. They could have been anyone. He kept sailing until they blocked us with a bigger boat and sent armed soldiers on from a second smaller one. I later learned they’d pirated the first boat at around 4am; they’d jammed our comms and internet so that we couldn’t give each other, or the outside world, much warning. We had not quite reached the same vertical axis as Port Said in Egypt; we were, in other words, nowhere fucking near Israel.

From there they transferred everyone from the small ships to a huge military boat, locked us in the cabins and sailed it for twelve hours to Ashdod port. Their propaganda cameras were still rolling at this stage so there was no physical aggression. The moment I stepped off that boat, it was surveillance cameras only. The instant change was marked by two police officers shoving my head down, pushing my arms behind my back, dragging me forwards and yelling at me to kneel.

At port security they pushed me through the first of what would be many body searches (‘Legs wider, legs wider’), interrogations (‘So you’re a journalist? Do you know the truth about [insert hasbara screed]?’), and demands to sign deportation orders without having spoken to lawyers and without having been accused of any crime. I didn’t sign. (They did not permit me to see a lawyer during any point of my five days in Israeli prison. It makes no real sense to handle us under immigration law, since Israel’s legal argument for stopping the boats is not that we are trying to enter their territory but that we are trying to breach their blockade of someone else’s – something that is not, as far as I am aware, chargeable as a criminal offence or punishable beyond thwarting the attempt. But expecting rule of law from a genocidaire is, perhaps, ambitious.)

Then they cable-tied my hands so tightly that it hurt and I lost circulation, blindfolded me and hurried me through to the back of a mysterious room or large vehicle — ‘Yalla, yalla’, a difficult command to follow when navigating steps without the use of your eyes or hands. Eventually someone shoved me along again to what I can only guess was a small prison van; I could feel with my feet that there were only a few centimetres of space between me and the door, and once it was moving, it became clear we were in the back. There were four of us there, all bound and blindfolded. We had no idea where we were going or — still — what we’d even been accused of. I would later learn that the journey took around four hours and took us from Ashdod on the central coastline to Ktzi’ot prison near the southern border with Egypt.

I was losing feeling in my hands from my cable tie, and when they finally took them off the skin had purpled. The woman beside me had it far worse: they’d handcuffed her so tightly that she was screaming in pain before the van had even departed. When they eventually tried to remove the cuffs, it took several attempts because of how badly her flesh had swollen over the metal. There were several such cases throughout our time there; I saw multiple people’s marks.

We spent Wednesday, Thursday and Friday in Ktzi’ot, a prison notorious for torturing Palestinians. My understanding is that the flotilla participants who’d signed at the port were released after around two days*. I and the others who’d refused were then transferred to Givon prison near Tel Aviv. The physical conditions of the jail were on the whole slightly better — Givon is an immigration prison, not a ‘terrorist’ prison — but the guards knew we were the problem cases and raised their aggression and petty cruelty accordingly. They had a particular animus against my cell, the Problem Cell, because we were always singing and banging on the door, but their retaliations only made us more determined and more organised. This, naturally, infuriated them all the more; they wanted us to lose our humanity. Their most aggressive barge-in — there was one every two hours or so, generally five or six armed men, sometimes one or two women if they wanted to arbitrarily search us in the bathroom — happened not when we’d been making noise, but when they saw on the camera that our cell had been taking turns leading exercise sessions and discussion circles.

Most of us were refusing food, and this bothered them too; any reminder that we were political prisoners did. I didn’t eat during the five days I spent in jail, and some still there from Sumud went longer.

I’d determined in advance that I’d probably be in jail too long to refuse water, too, without permanent kidney damage, but here I hit a different hurdle: there was no safe drinking water anyway. In both prisons they told us to drink the brown tap water. It never ran quite clear in the first one; in the second it eventually did, but it still smelled strongly of chlorine. I got a UTI from drinking it and wound up having to explain this to five men with guns and the male medic they’d summoned at my cell door. None of them had any idea what I was talking about. ‘Can I have two litres of clean water a day and a change of underwear so I’m not wearing the same ones for days on end?’ I said. They laughed to themselves, said maybe, maybe, and left. Nothing happened, of course. Often when people were banging on the doors, it was to demand basic medical care that never came.

They were fond of collective punishment, too: they threatened my whole cell with tear gas, and that night crammed eleven of us into a five-person room, because I and a couple of others had been banging on the door for news of a friend we’d heard them beating. They wanted to pierce our unity, but they never succeeded. ‘Non, rien de rien’, I sang on the last day as an officer hurried me away from one of the French women I’d been in the loathed Problem Cell with; ‘non, je ne regrette rien’, we continued until we could no longer hear each other.

I won’t get into everything that happened; this is already longer than I’d intended. The worst they did to me personally was shoving, no drinkable water, medical neglect and temporary nerve damage from hand restraint. Others were punched, beaten, put in solitary confinement for days on end. They targeted Jews and racialised abductees. There were a few scoffs about Ireland when the officers asked my nationality, and a very strange moment during the illegal interception of my boat (‘Why are you speaking Irish?’ an officer demanded to a couple of us; the answer was genuinely ‘Because we normally do’). Overall, though, I got more or less the standard white-woman-with-EU-passport treatment. That is to say: all of what I’ve detailed above constitutes a Michelin-rated five-star encounter with Israeli prison guards. They are unimaginably worse to Palestinians.

This is them when they’re holding back. With Palestinians, they torture people to death, sexually abuse them and keep them for months, years, decades, often without charge. In my first cell in Ktzi’ot, most of the writing on the wall — I don’t know how they smuggled in pens despite a strip search but someone managed — was in Arabic. Opposite our window was a poster of a road in Gaza reduced to rubble. The caption in Arabic, evidently targeted at the jail’s usual captives, said: the new Gaza.

There are over 11,000 Palestinians in Israeli captivity, including at least 400 children. The ceasefire will not bring most of them any immediate prospect of release. People in Gaza are returning to rubble under an agreement that will not even let them vote.

Palestinians in Gaza can rest if they want to. The rest of us need to keep the work up. The next time I can join a flotilla again, I will.

*That said, there were certain people we were fairly sure had not signed who left after two days. This happened on Sumud as well; the explanation I’ve heard going around is that certain countries have arrangements with Israel to get people out quickly regardless of whether they sign.

Thank you for what you and others have done, and for consistently pointing out the horror that Palestinians endure in Israeli jails. Glad you’re back home and safe N. 💙

Thank you for drawing attention to this at such personal cost.